- Jay Parsons' Rental Housing Economics

- Posts

- Top 11 Myths on Institutional Investors of Single-Family Homes

Top 11 Myths on Institutional Investors of Single-Family Homes

What does the data and academic research show about the realities of institutional single-family rental investors? It's more nuanced than meets the eye.

Narratives are Running Away from Realities

I recently saw a survey showing nearly half of Americans blame “investors using housing as profit” as the primary reason for high home prices. It’s a rare topic that unites portions of the left and the right, as President Trump’s proposed ban on institutional homebuying brings together an unlikely alliance of free-market capitalists and pro-diversity progressives. Both sides are seemingly unaware they’re undermining their own causes, likely due to narratives detached from realities. Perhaps the best example of detachment from reality is the fact that many Americans still think BlackRock owns houses (they don’t).

However, in fairness, clearly Americans are frustrated about housing affordability. And for good reason!. The pain is real.

But chasing a boogeyman won’t make housing more affordable. If we’re serious about solving housing affordability and availability, the most compassionate and most serious thing we can do is discard wildly held conspiracy theories — and instead focus on proven solutions that can move the needle. This post is intended to use data and academic research to deflate those myths.

Here are the Top 11 widely held myths about institutional investors, along with research and data for your consideration in debunking them.

(Also, if you prefer listening versus reading, check out the podcast version of this post on Spotify, Apple, or YouTube. Or if you missed my previous newsletter breaking down what we do and don’t know about the proposed ban, check it out here.)

Myth 1: “Institutional investors are buying 25% of homes for sale!”

Reality: It’s never been anywhere near that level – and in more recent times, institutions have sold more homes than they’ve bought.

Confusion stems from too many people using “institutions” and “investors” interchangeably. But the vast majority of SFR investors/buyers are mom-and-pop businesses, not Wall Street.

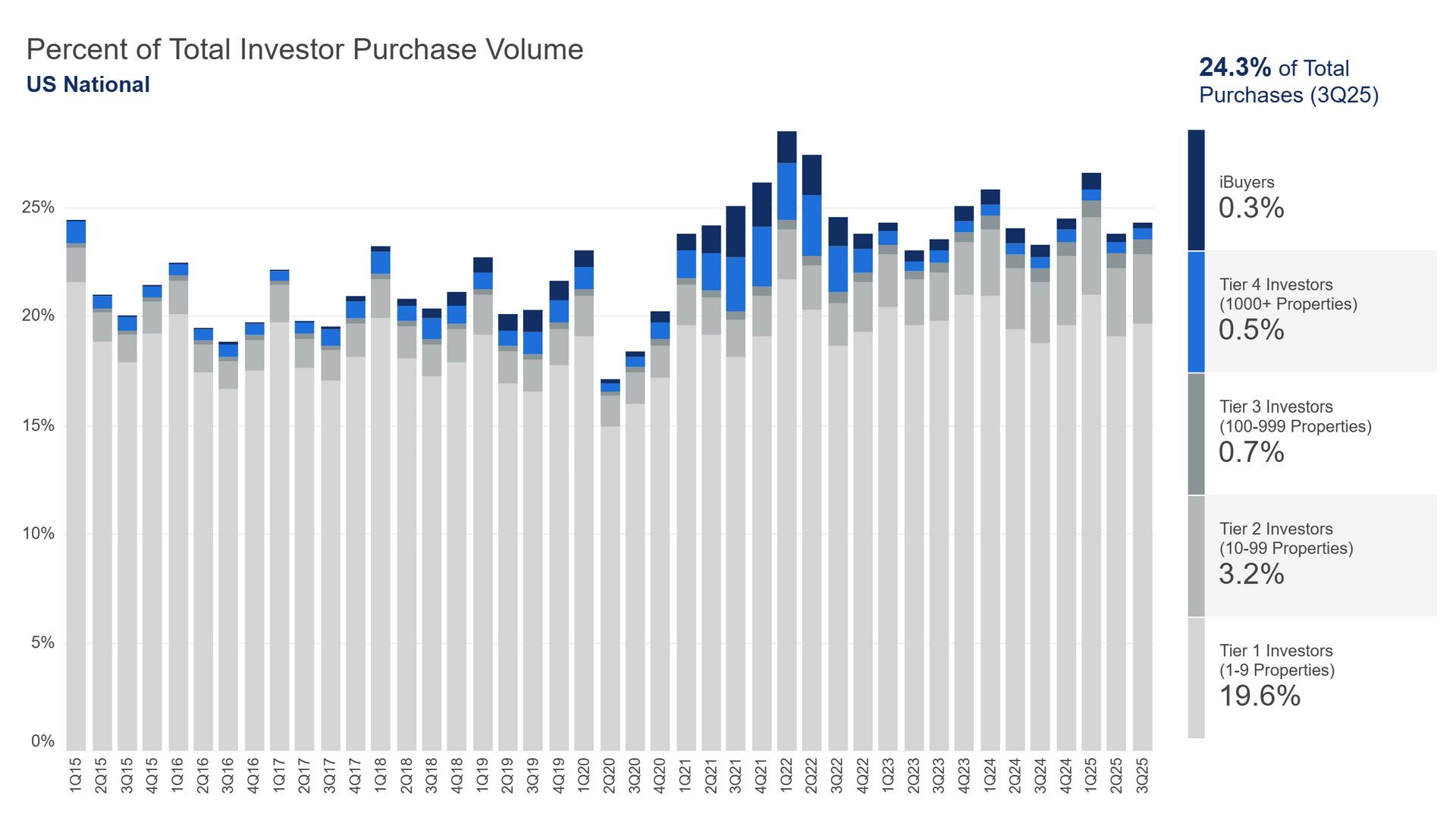

Data from John Burns Research and Consulting shows institutional investors represent 0.5% of single-family home sales. And it’s never even reached 3% of sales in their data.

By comparison, small investors with 1-9 properties tend to be around 20% of home sales. So the vast, vast majority of time you see investors buying houses, it’s a small family business or local group. (Also: Even some small investors use LLCs for liability protections, so an LLC doesn’t necessarily mean a large corporation.)

Source: John Burns Research and Consulting

So any ban on institutional buyers would be removing just a tiny sliver – 0.5% of the buyer pool.

Additionally: Headlines typically only look at ACQUISTIONS, while ignoring DISPOSITIONS (sales). It’s net flows that matter most, particularly when/if investors sell homes in better condition than when they bought them.

Data provider BatchData wrote: “The perception that institutional investors are gobbling up the nation’s housing stock is overstated … In Q2 2025, large institutional investors sold 5,801 properties but purchased only 4,069, marking their sixth consecutive quarter as net sellers.”

“In Q2 2025, large institutional investors sold 5,801 properties but purchased only 4,069, marking their sixth consecutive quarter as net sellers.”

For those arguing: It’s not the national numbers, but it’s cities like Atlanta,” please jump to Myth #10.

Myth 2: “Renters will become homebuyers if institutions weren’t buying all the homes!”

Reality: The theory may sound intuitive, but it’s based on an illogical premise. How so?

Three reasons:

That view assumes that every home bought by an institution would have otherwise gone to an individual homebuyer. But remember: Mom-and-pop investors outnumber institutional investors by around 40-to-1. So the biggest SFR investors are still there. Peer-reviewed academic research shows that if institutions were banned from buying homes, smaller investors – not individual homebuyers – would purchase the majority of those homes.

Many SFR renters choose to rent for lifestyle reasons – wanting to maintain flexibility to relocate, wanting to live in higher-end neighborhoods with access to better schools, or wanting to avoid paying for maintenance and property taxes.

And most importantly: Unfortunately, most SFR renters aren’t in position to just buy a house. Let’s dig in more on this one:

Stephen Scherr, the co-president of Pretium (the nation’s largest SFR owner) told CNBC that their typical renter household income is $130,000, and yet 90% of their renters cannot qualify for a mortgage.

Another institutional SFR executive, Amherst CEO Sean Dobson, told Bloomberg TV: “All [the ban] does is make it more difficult for platforms like ours to provide more housing opportunities to that cross section of the population that is not served by the mortgage market … When we sat down with the most ardent critics of our business and they really understood the financial profile of the customer we serve — someone with a 625 FICO who’s living in a $350,000 house for $2,000 month, they realize there’s no better solution than the one we provide.”

So even a moderate decline in home prices isn’t going to help people buy if they still have bad credit and if they still don’t have enough cash for a down payment.

That ties into another data point here… In a 2025 survey of single-family renters by the Center for Generational Kinetics, renters were asked to pick the top three financial barriers to buying a home. Not surprisingly, home prices were No. 1, yet only about half of renters (55%) picked that option.

The next four most common reasons:

My credit score is too low

I can’t afford the down payment

Interest rates are too high.

Property taxes are too high.

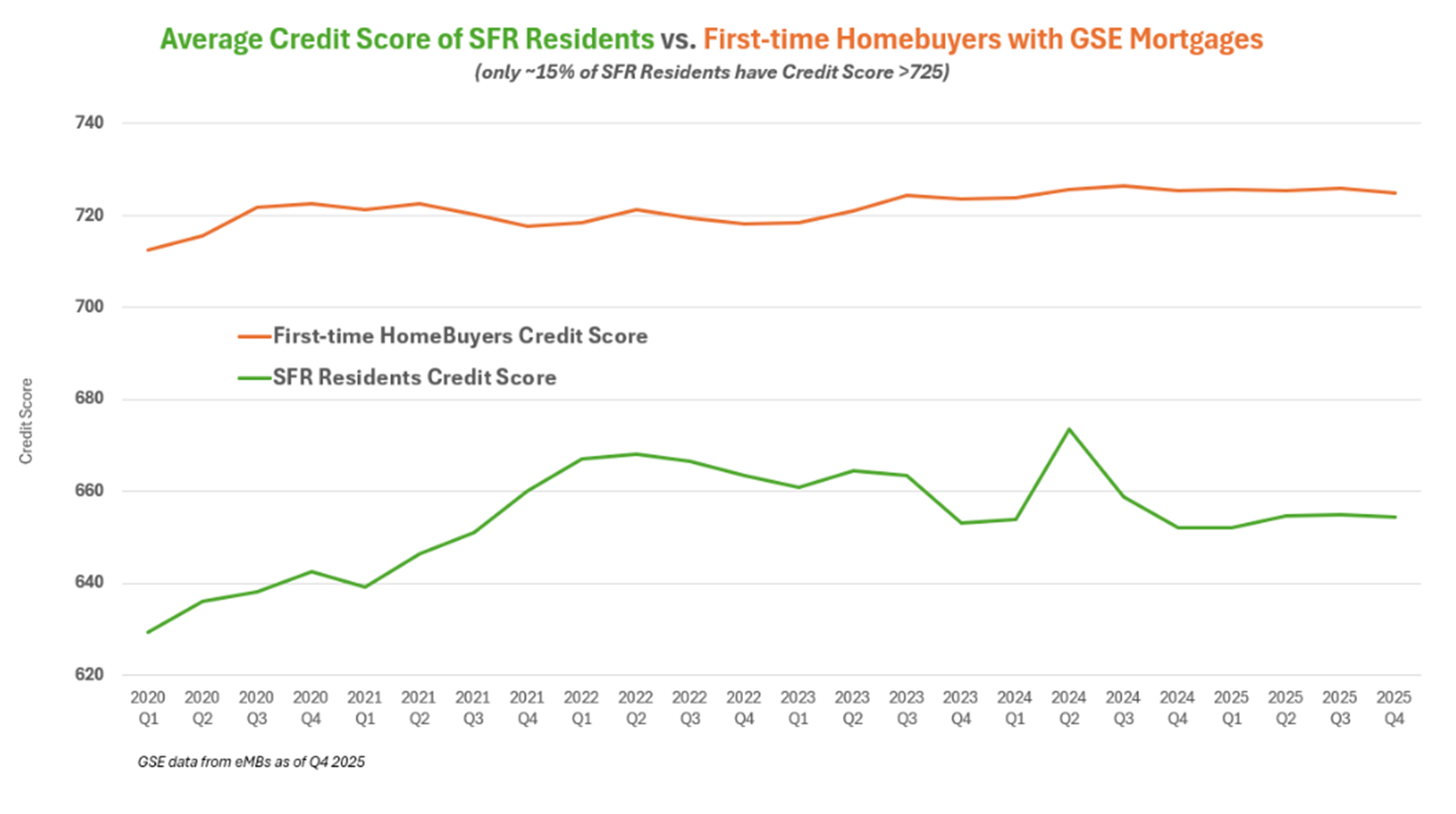

One national SFR operator shared with me this chart (re-sharing anonymously with their permission) showing credit scores of their residents versus credit scores for first-time homebuyers with an agency-backed mortgage. Look at that gap: Renters have credit scores below 660, while first-time homebuyers are above 720.

Credit scores for a national SFR operators’ residents versus first-time homebuyers.

So we need to address that ROOT ISSUE of affordability if we really want to move the needle on helping more renters buy homes. And, frankly, we should do that because when more people are buying homes, we tend to see better economic growth and household formation, too.

Myth 3: “Institutional landlords are pushing up home prices, pricing out homebuyers!”

Reality: Well, the reality is nearly half of Americans seem to believe this, according to a 2025 survey citing “investors using housing for profit” as a top perceived reason for high housing prices.

But what does the data and academic research say?

Here’s the punchline: Every sale plays a role in setting prices, of course, so institutional buyers do have some impact. But there’s ample research showing that the impact is much smaller than people think.

Freddie Mac researchers conducted an extensive analysis of the post-COVID homebuying boom driving up prices in 2022, and they concluded this: “What may surprise you is that investors don’t make our list of top drivers” of home price growth. Instead, Freddie linked price growth in that era to less-sexy reasons: low mortgage rates, under-building, an increasing number of first-time homebuyers due to demographics, and increased migrations from high-cost cities into lower-cost areas already wrestling with low supply.

Joshua Coven’s research (which was co-winner of the American Real Estate & Urban Economics Association’s award for best doctoral dissertation in January 2026) found that while institutions impact home prices, “the price impact is far below the observed association between institutional investor purchases and actual price increases.”

Some will argue: It’s not about the national numbers … you have to look at markets with high concentrations of institutional owners. We’ll tackle more on this later (See Myth 10), but it’s worth noting researchers from the American Enterprise Institute found no correlation between institutional concentration and home price growth. They wrote:

“If institutional investors were the prime driver of prices, the hard causality pattern would be hard to miss. But not so much in reality. Since 2012, national home prices have risen roughly 150 percent, yet some of the fastest-growing markets—including San Jose, Bend, and Providence—have virtually no institutional presence. Meanwhile, several metros with higher investor shares have seen below-average price growth. Econ 101 scarcity, not financialization, does the heavy lifting here.”

In fairness: Yes, you will find other research arguing that the impact is more significant. However, some of that research traces back to post-GFC era when homebuyers were largely sidelined and that “rescue capital” contributed to reversing the long drop in home prices, thereby helping homeowners reverse equity losses. Researchers from the University of Texas at Dallas wrote: “These findings demonstrate how investor activity can stabilize housing prices in distressed markets, which helps protect the value of neighboring homeowners’ equity.”

So it’s revisionist history to say only they increased home prices in that era without including that context. (And furthermore, if you remove institutional capital, you remove their ability to stabilize a declining market where individual buyers were sidelined like they were in the early 2010s.)

Myth 4: “Institutional investors are creating bidding wars and pushing out regular homebuyers with all-cash offers!”

Reality: This is one of the best examples of public misunderstanding for institutional investment business models – and likely conflating “institutional investors” with other types of cash buyers.

Unlike individual homebuyers, investors prioritize cap rates / yields, and market-topping prices would crush yields.

Institutions hunt for value – often even below what first-time homebuyers could consider because investors favor undervalued homes often requiring major repairs. As Freddie noted: “Institutional and small investors both heavily target under-market-value homes that need more repair than what most first-time homebuyers are willing to invest.”

“Institutional and small investors both heavily target under-market-value homes that need more repair than what most first-time homebuyers are willing to invest.”

Remember that individual homebuyers may have trouble financing homes requiring heavy repairs, so they would need more upfront cash to pay for it. Larger SFR players (or even small investors with handyman skills) have a significant advantage because they have in-house crews and efficiencies of scale. In turn, that boosts the quality of aging housing stock that most homebuyers couldn’t handle themselves.

Additionally, institutional SFR investors have strict buy boxes – likely to be more disciplined than some of the wild stories we heard about certain iBuyers (who we shouldn’t conflate with institutional SFR). As one writer put it: “Institutions struggle to compete against owner-occupants when buying homes. Institutions typically underwrite conservatively, tying purchase prices to local rents and strict financing limitations. They rarely outbid families.”

Also, there’s this: Academic research shows it’s usually a losing financial proposition to win a bidding war on a house. That math matters more to an investor than to an individual homebuyer looking for a long-term home.

That’s not to say an investor never wins a bidding war, but there’s no real data showing this is a common occurrence.

Myth 5: “Institutional investors with all-cash offers are buying cheaper homes that would otherwise go to first-time homebuyers!”

Reality: This is another gross oversimplification. Let’s circle back to what Freddie Mac researchers found in 2022: “Most investor purchases were for deeply discounted homes priced below the typical home bought by first-time homebuyers.”

And: “Institutional and small investors both heavily target under-market-value homes that need more repair than what most first-time homebuyers are willing to invest. Half of institutional investor purchases in 2020 were priced below the lower quartile price paid by first-time homebuyers.”

Researchers at the Urban Institute found that institutional investors spend far more on repairs than do traditional homeowners when buying a house.

For homes in disrepair, investors “can pay cash sourced from capital markets, whereas owner-occupants often need a rehabilitation mortgage that is typically more expensive and difficult to acquire than a standard home purchase mortgage.”

Given those realities, it’s no surprise that Coven found that even if institutional investors were removed from the market, more than 60% of the homes they bought would otherwise have been acquired NOT by individual homebuyers, but by smaller investors.

This isn’t to say there’s zero competition with first-time homebuyers. It happens, yes, but it’s not nearly the phenomenon it’s portrayed to be.

So when you hear about how institutions own starter homes that could have gone to first-time homebuyers, intellectual honesty requires acknowledging two realities:

First-time homebuyers could not have bought many of those same houses given challenges financing homes in disrepair (or additional cash needed) … only AFTER the investor completed repairs.

Plus: Institutions were more actively buying starter homes in the 2010s when prices were cheap and homebuyers mostly sidelined. As home prices have jumped, institutions have pulled back on buying one-off houses and instead focused on new construction and smaller SFR portfolios.

Myth 6: “Institutional investors are letting houses fall into disrepair!”

Reality: They spend a lot of money on repairs, and a new survey shows renters rate larger property managers more favorably for maintenance.

Here’s what researchers at the Urban Institute found: “Two of the largest single-family institutional buyers’ annual reports illustrate the substantial amount institutional investors spend on these renovations, even with the volume discounts. The Invitation Homes 10-K indicates that it spent $39,000 per home for up-front renovations completed during 2020. American Homes 4 Rent’s 10-K for 2020 notes that they typically spend between $15,000 and $30,000 to renovate a home acquired through traditional acquisition channels. This is considerably more than the $6,300 we calculate the typical homeowner spends during the first year after purchasing a home.”

Additionally, the Center for Generational Kinetics’ 2025 survey shows single-family renters actually view professional property management companies (such as institutions and other large investors) more favorably than mom-and-pop investors for maintenance-related issues.

In the survey, SFR renters surveyed were asked the top advantages of renting from a professional property manager, and the top two reasons were both maintenance related – “reliable and timely response to maintenance requests” and “access to 24/7 emergency maintenance services.” On the flip side, renters scored small operators lowest on maintenance-related issues.

(In fairness to mom-and-pops, SFR renters in the survey said the top advantage of renting with a small operator is a “stronger personal relationship.” So clearly there are benefits to both depending on what you value most.)

Myth 7: “Institutional investors are driving down homeownership! You will own nothing and be happy!”

Reality: This is one of the more bizarre myths out there because all you have to do is Google the homeownership rate.

Let’s break this down going back to the Great Financial Crisis to set proper context.

Chapter 1: Homeownership rate soars between 1995 and 2004, setting a record high in Q2’04 at 69.2%, then hovering all that high-water mark through early 2007.

Chapter 2: The housing bubble busts. Crisis. Foreclosures – combined with significantly tightened lending standards, particularly for subprime borrowers with weaker credit – push down homeownership to a low of 62.9% by Q2’16. Banks and regulators then had to wrestle with millions of foreclosed homes in REO. Most of them homes sat vacant when investors (including institutions) started buying them (some in bulk sales on courthouse steps), converting vacant formerly owner-occupied homes into occupied rental homes.

Chapter 3: Too many people stopped following this saga after Chapter 2 and therefore still have dated perceptions, but Chapter 3 is critical.

Individual homebuyers flipped the switch starting in 2016. Homeownership trended UP between 2016 and 2023 (from 62.9% back up to 66.0%), largely because INDIVIDUAL HOMEBUYERS outmuscled investors for market share. In fact, over that period, we CONVERTED 1.5 million for-rent homes into for-sale homes. How? Why?

As John Burns wrote: “The number of rental homes in America began declining as many smaller investors sold their homes for a profit. This decline received almost no attention in the press.”

Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies said the same thing: “The number of single-family rentals then fell in more recent years as the for-sale market strengthened, and many of these homes converted back to owner occupancy.”

“The number of single-family rentals then fell in more recent years as the for-sale market strengthened, and many of these homes converted back to owner occupancy.”

In other words: As homebuyers re-entered the market and prices climbed, some small investors took advantage of higher prices by selling. Individual homebuyers were the primary beneficiary, taking 1.5 million homes back into the owner-occupied pool.

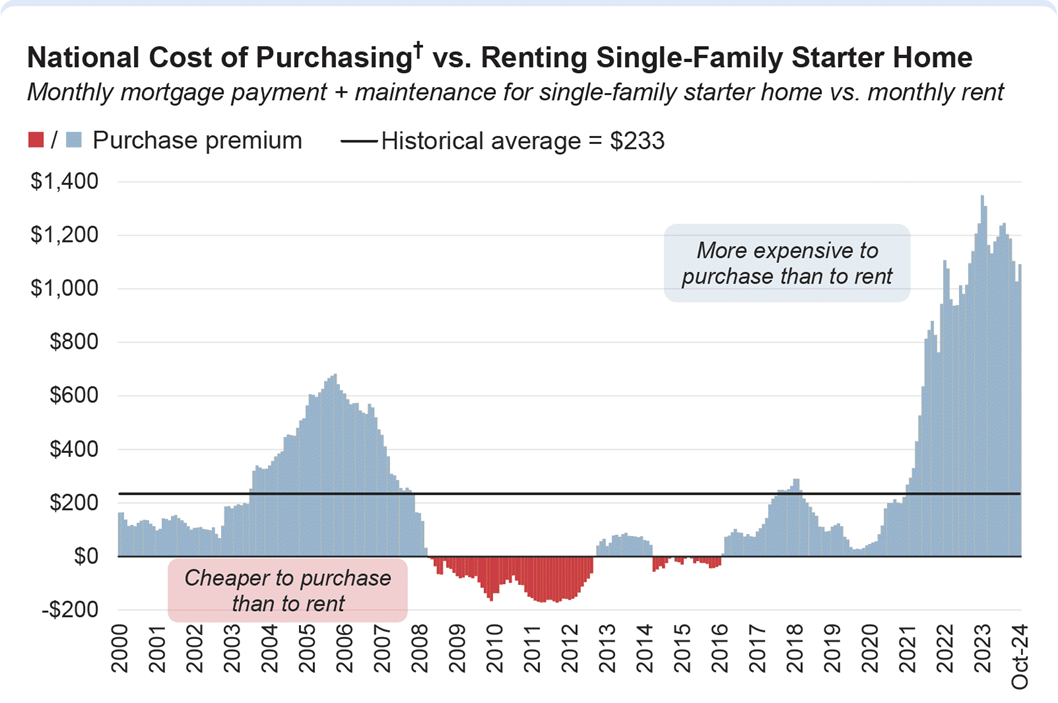

And then onto Chapter 4) Mortgage rates spike, home prices are high, and now there’s a premium of >$1,000 in additional monthly costs versus renting a single-family home.

Source: John Burns Research and Consulting

So now we’ve seen a modest decline in homeownership, from 66% in 2023 to 65.3% as of Q3’25. So we’re down 70 bps. But remember, over that period, institutional investors have been largely sidelined, as well, holding at around 0.5% share of home sales. Some of the reduction in homeownership seems traced to “accidental landlords” – individual homeowners renting out their homes instead of selling for various reasons.

So again, the facts do matter. And while homeownership today is still lower than it was at the height of the housing bubble, we know in hindsight that homeownership back then was propped up by subprime mortgage lending. Such borrowers are far less likely to qualify for mortgages today due to Dodd-Frank legislation, so it’s no surprise to hear the nation’s largest SFR owner (Pretium) say 90% of their renters can’t qualify for a mortgage.

Comparing any metric against its all-time high is probably not proper context. Taking a broader view, the Q3’25 homeownership rate of 65.3% matches the long-term average. And if you like medians better than means, we’re actually above the long-term median of 64.8%.

Myth 8: “Institutional investors are bad landlords!”

Reality: “Good” or “bad” can be subjective based on one’s personal experience (and certainly – like any business or even government service – bad experiences can happen), but there’s little credible data to support the narratives.

CGK’s 2025 single-family renter survey found only 18% of SFR renters said they have a “difficult relationship” with their landlord or property manager. And of course, we tend to hear from those 18%. We should certainly address their concerns, but it’s important to remember they’re not the majority by any means.

Housing researcher Laurie Goodman at the Urban Institute wrote this back in 2017: “There is no credible evidence that institutions make worse landlords than mom-and-pop companies. These investors will, by necessity and competition, bring professional standards and methods to managing these properties, making them more like their larger apartment building brethren.”

This is an important point of logic that is often lost in public dialogues.

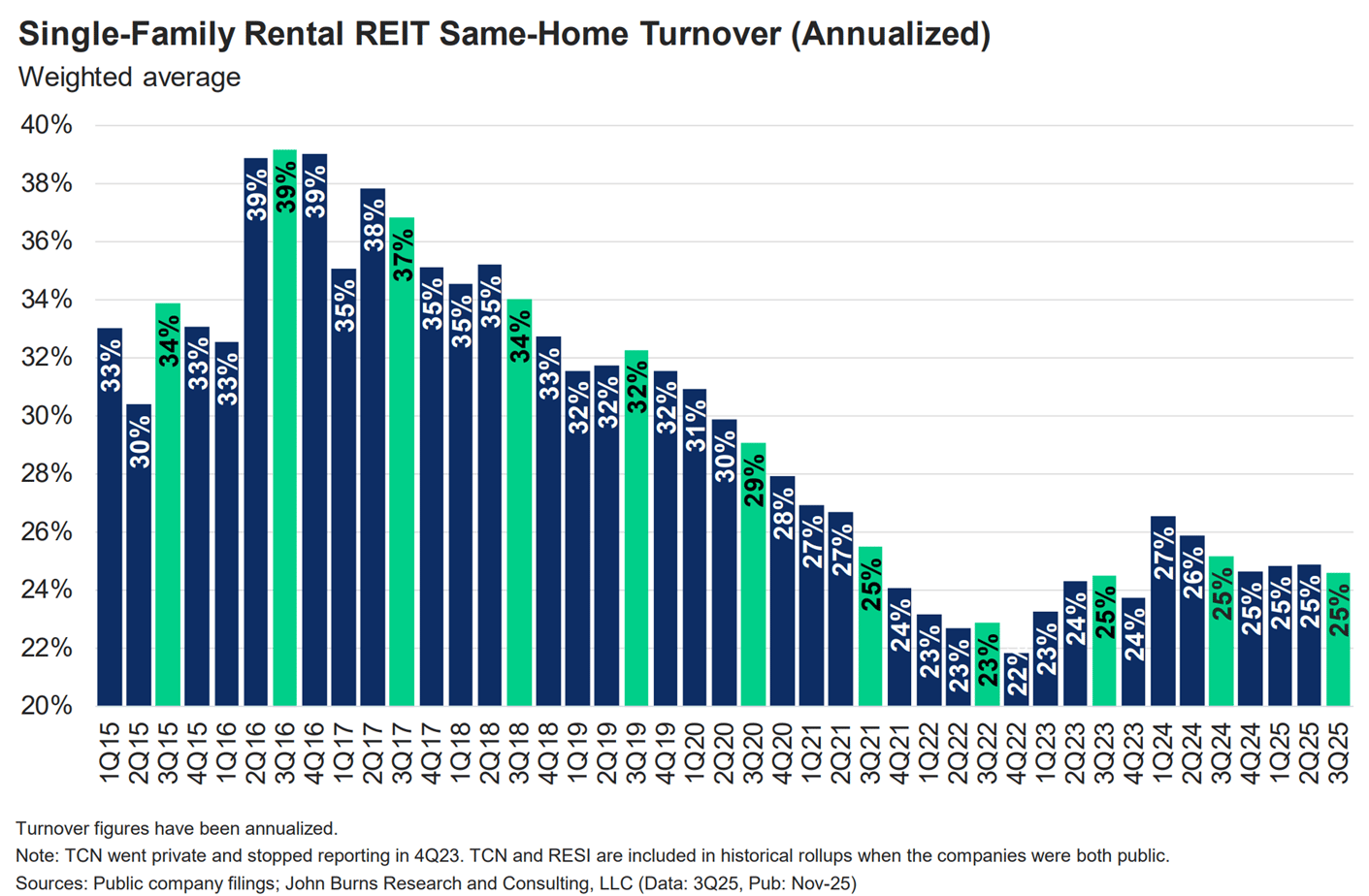

From a pure business standpoint, SFR operators – like most businesses in a fragmented industry – are highly incentivized to create good experiences for their customers. And the data bears this out. The most recent data from SFR REITs show their turnover rates have continually declined over the last 10 years (and this trend continued even when mortgage rates were cheap) – and are now around just 25%.

Source: John Burns Research and Consulting

Even now, we see the number of SFR listings on the market has spiked, renters have options even if they can’t buy a house right now, and an increasing share are choosing to stay. If it were as bad as some people think, we would have a lot more turnover than we do. Rather, the steady decline in turnover likely reflects (at least in part, among other factors) improving property management. (Remember: Institutional SFR was a nascent business 15 years ago.)

So, again: Even if you think institutional investors are cold-hearted profit seekers, you’d have to acknowledge institutions are financially incentivized to provide a good experience for their customers (renters).

Myth 9: “Institutional landlords increase rents more!”

Reality: This is another topic that gets grossly oversimplified, even by some academic researchers.

Many critics cite this report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Here’s one sentence often quoted: “Studies GAO reviewed found that institutional investors may have contributed to increasing home prices and rents and helped stabilize neighborhoods following the financial crisis.”

Too many people stopped reading right there, and failed to understand the context.

That last part is really important context. It said: “following the financial crisis.” If you actually read the report, it’s talking about the early 2010s decade. As noted earlier, there is indeed ample evidence that institutional investors helped stabilize the housing market during the GFC – helping to end declines in prices and rents, starting the recovery (and slow rebound in prices/rents).

So, what about since then? Again, if you actually read the GAO report, you’ll find it cites multiple studies with conflicting views on the impact of institutional investors on rents, and ultimately the GAO report is inconclusive.

Why would it be inconclusive?

As Laurie Goodman and Robert Abare wrote for the Urban Institute: “These investments don’t push rents higher because rent prices remain a product of supply and demand.”

To that point, we DO see a much more indisputable correlation. In recent years, markets with higher shares of institutional investors have seen LESS single-family rent growth than markets with low shares of institutional investors.

Why is that?

It’s not because of altruism. It’s supply and demand. Institutions not only buy houses, but they also build a lot of housing (which has been preferred strategy in recent years) – including apartments, build-to-rent single-family homes and for-sale homes. All that added supply puts downward pressure on rents and on prices.

Coven’s 2025 research paper found institutional investment led to LOWER rents, not higher rents for those exact reasons.

He wrote: “Institutional investors increase the quantity of rentals and lower rents on net because their ability to operate large portfolios at scale outweighs the incentive to use market power to decrease the rental supply.” (To be clear: Coven is not saying institutions cut rents altruistically, but that their presence resulted in lower rents than otherwise because of the additional supply impact.)

Translation: More scale = more supply = lower costs for operators (due to scale) + lower rents for renters (due to increased competition).

On that note, it’s important to understand how institutional investment models work. Their goals are not to chase highest rent growth, no matter how many times cynics say it. Their goal is generate value and yield – of which rent is just one component. Entry costs and ongoing operating expenses are huge pieces of the equation.

That’s why institutions prefer markets like Atlanta where they can achieve larger scale and therefore drive more operational efficiency (lower cost). Having large scale allows them to do things they couldn’t do with only a handful of properties – like hiring full-time maintenance teams and having extra materials/appliances on hand when needed. That, in turn, benefits renters when a maintenance challenge pops up.

More on that in Myth #10.

Myth 10: “National stats don’t matter! Just look at markets like Atlanta where institutions are buying everything!”

Reality: It’s true that institutions favor markets where they can build scale. But there’s more to it than meets the eye. Let’s break down the two perceptions we hear a lot.

One: “Home prices are rising more in institutionally favored markets like Atlanta because institutions are driving up prices.”

And two: “Rents are rising more in institutional markets like Atlanta because institutions are driving up rents.”

Let’s take the statement first about home prices.

In a piece titled “America’s Housing Crunch Has the Wrong Villain,” the American Enterprise Institute found: “Institutional ownership is highly concentrated by geography: Five percent of counties hold a whopping 80 percent of institutionally owned homes. And more than half of US counties have none at all. Also: No county exceeds a 10 percent ownership share. Even in frequently cited metros such as Atlanta and Houston, institutional ownership sits in the low single digits. Most ZIP codes are far below even those levels.”

AEI also writes: “If institutional investors were the prime driver of prices, the hard causality pattern would be hard to miss. But not so much in reality. Since 2012, national home prices have risen roughly 150 percent, yet some of the fastest-growing markets—including San Jose, Bend, and Providence—have virtually no institutional presence. Meanwhile, several metros with higher investor shares have seen below-average price growth. Econ 101 scarcity, not financialization, does the heavy lifting here.”

And what about rents?

Here’s what Coven found in his 2025 research (as cited earlier): “Institutional investors increase the quantity of rentals and lower rents on net because their ability to operate large portfolios at scale outweighs the incentive to use market power to decrease the rental supply.”

What Coven is writing here is critically important nuance often overlooked in media coverage and in policy debates – again reflecting the importance of understanding institutional business models.

Most people see scale as a bad thing. The assumption is that if one particular institutional firm has hundreds or thousands of rental homes in a given metro area, they somehow have massive pricing power. But this flawed for several reasons:

In a market like Atlanta, even the largest SFR operators owns less than 5% of the single-family rentals. So while the total number of homes is large, context is important. A low single-digit market share won’t give you much pricing power in any industry, and SFR is no exception.

But more importantly, it’s not about rents so much as it’s about OPERATING COSTS.

Here’s an example: If one company (let’s call them HappyCo) owns 1,000 houses in Atlanta (which is a big number, but just for context, let’s point out that the equivalent of 3-4 apartment properties). With that scale, HappyCo can likely hire full-time maintenance teams and stock extra supplies/appliances/parts on hand.

So when a resident moves out of a home, HappyCo can fix up that home FASTER and get it back on the market FASTER – thereby reducing what the industry calls “vacancy loss.” That means even absent higher rent, that property manager will make MORE money simply by reducing the number of days that home sat vacant.

That’s efficiency of scale. HappyCo’s operating costs per home are going to go down with more homes. Not just for maintenance, but could also go down for insurance and debt costs and technology, etc.

Scale helps improve operating expenses, which boosts net operating income – which helps improve value. NOI and valuations matter more to an investor than rent growth.

If institutions just wanted to chase rent growth, they’d all be flocking to cities in the Midwest and Northeast. But they don’t do that because that’s only one of many variables, and it’s harder to build scale in those regions and in high-cost coastal cities.

Myth 11: “There’s No Public Benefit to Institutional Investors Buying Houses!”

Reality: Everyone has their own takes, and that’s fine, but any consideration of a ban should at least consider benefits documented by academic research. Even if you’d prefer every house be owned by an owner-occupant, you should at least be aware of the unintended impacts of such policy.

Non-industry academic research shows institutional investors are more likely to improve the housing stock (by fixing homes in disrepair), provide stability and liquidity to the housing market (as occurred in early 2010s), diversify neighborhoods with families who couldn’t otherwise live there, and increase the total housing supply.

Some of the most compelling positive evidence is on upward mobility of families unable to buy homes in lower-poverty neighborhoods with access to better schools. This is notable because research shows institutional investors are more likely to invest in higher-income areas, while local investors are usually the opposite.

One academic paper noted that “… children are experiencing substantial achievement gains from attending higher-performing schools.”

Another paper led by Harvard economist Raj Chetty draws broader conclusions (not limited to SFR) on the positive societal impacts for families moving from high-poverty areas into lower-poverty areas: “We find robust evidence that children who moved to lower-poverty areas when they were young (below age 13) are more likely to attend college and have substantially higher incomes as adults. These children also live in better neighborhoods themselves as adults and are less likely to become single parents themselves.”

Another researcher noted: “Institutional investors help make the housing market more liquid and less cyclical. They upgrade the quality of the housing stock, typically at lower cost than smaller renovation outfits. They make desirable neighborhoods accessible for households that could not afford to buy in those neighborhoods. Increasingly, they are directly increasing housing supply.”

And the Urban Institute shared how scale can help renters: “Because of their size, scale, and organizational infrastructure, mega and smaller national single-family rentals can improve the rental experience. Institutional investors’ practices have an impact on hundreds of thousands of renter households and have the potential to set new standards for practice in the rental market. And it is often more feasible for institutional investors than for their mom-and-pop counterparts to implement certain important practices, such as rent reporting.”

— My Latest Posts on LinkedIn —

Here are some recent posts if you missed them:

In a twist of irony, just days before President Trump announced a proposed ban on institutional investors in single-family homes, the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association awarded a paper titled: “The Impact of Institutional Investors on Homeownership and Neighborhood Access”

Apartment operators will probably hear a lot more about “gain to lease” and “inverted rent rolls” here in 2026.

Newly released inflation data shows rents continue to cool, and that’ll likely remain the story for CPI Shelter in 2026 due to lag effects.

This article in The Wall Street Journal shows us why the best tenant protection is to build a lot more housing.

Here’s everything we know (and don’t know) about President Trump’s proposed ban on institutional investors from buying houses.

There are many proposed flaws in the arguments for banning institutions from buying houses, starting with the myth that single-family rental supply is increasing as investors take houses into the rental market.

— Now Spinning on The Rent Roll Podcast —

For 2025, The Rent Roll with Jay Parsons podcast ranked in Spotify’s top 2% of podcasts for minutes played and in the top 1% for most shared shows. Additionally, The Rent Roll continues to frequently rank on Apple’s charts for investing-themed podcasts, and was recently ranked as the third-best podcast in all commercial real estate (and #1 in housing) by the readers of CRE Daily!

Thank you to everyone who’s made The Rent Roll part of your weekly routine! New episodes are released every Thursday morning.

Episode 67: Top 10 Myths About Institutional Investors in Housing with Baruch College’s Joshua Coven.

Episode 66: Q1'26 SFR/BTR Update and Outlook with NexMetro’s Josh Hartmann

Episode 65: 15 Predictions for Apartments and SFR in 2026 with JBREC’s John Burns

Episode 64: What I Got Wrong (and Right!) in 2025 … Plus a multifamily capital markets update with Newmark’s Mike Wolfson

Episode 63: Green Shoots in Multifamily? Maybe. With CAPREIT’s Andrew Kadish

Episode 62: How Greystar Sees Property Management with Greystar’s Toni Eubanks

Episode 61: A.I. and Rental Housing with Funnel’s Tyler Christiansen